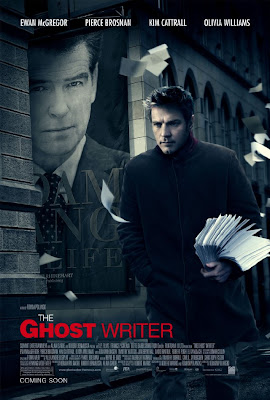

The Cricket only just now caught The Ghost Writer (2010) by Roman Polanski. It’s an interesting movie – and when saying “interesting” you may detect a hint of reservations. The story has ambitions that unfortunately remain unrealized. The unnamed eponymous ghost writer (Ewan McGregor) is hired to rewrite the memoirs of the former British Prime Minister Adam Lang (Pierce Brosnan) – a barely disguised stand-in for Tony Blair. Lang’s previous ghost writer just died from drowning under suspicious circumstances. When the writer moves from London to the U.S., where Lang is staying for a lecture tour (the town is a fictional Old Haven, on an island off Massachusetts, thus Martha’s Vineyard), a conspiracy slowly starts to unfold. Not only was the ghost writer’s predecessor murdered, Lang is accused of illegally extraditing terrorist suspects to the U.S. and faces possible war crime charges in The Hague. The writer discovers a connection between Lang and the CIA, involving a Cambridge classmate, Paul Emmett (Tom Wilkinson), who is now a Harvard professor. Additionally, it becomes clear that Lang is having an affair with his personal assistant Amelia Bly (Kim Cattrall), while his wife Ruth (Olivia Williams) grows evermore impatient at her husband’s unwillingness to take her advice as he used to. The ghost writer gets chased around and eventually contacts Lang’s former Foreign Minister Richard Rycart (Robert Pugh), who is now the U.N. envoy who accuses Lang of the illegal seizure of terrorist suspects.

The film – and the novel by Robert Harris on which it is based – poses some appropriate questions about the post 9-11 political landscape. Unfortunately, it never really explores these questions in any depth. It certainly is baffling that a Labour PM could have been such an American lapdog – especially at the time of the Bush administration. Adam Lang, however, remains a rather flat character, more of a womanizer and heavy drinker. We get no indication what motives him, why he is such a staunch pro-American, or what his thoughts are on the war on terror. We are led to believe that he merely became politically active through his wife Ruth, who was his trusted advisor for years. We get no indication either what motivates her, why she is throwing temper tantrums, or why she approaches the ghost writer for solace and sleeps with him. In the end, we learn that she has been a CIA agent from the start, recruited by Emmett, and thus her emotional instability becomes only more puzzling and her motivations even more obscure. There’s a hint at a rightist intellectual think-tank, Arcadia, with ties to the CIA and a weapons dealer in whose private jet Lang is flying. It is all tossed in our direction, perhaps even vindictively, for us to make sense of. But the moral quandaries, the fascinating grey area between good and bad, are left unaddressed. It is, for one, a government’s responsibility to protect its citizens, whether from terrorism or other menaces. How to implement national security without breaching human rights, international laws, and personal privacy, those are important questions from which this film shies away.

Even on the level of a thriller the movie falters. Polanski employs some of the usual ploys to create suspense: it rains a lot, skies are broodingly dark, much of the actions takes place on an isolated island, the ghost writer stays at an empty hotel, until a crowd of journalists and protesters swarm all over the place, Lang’s modern minimalist villa is menacingly impersonal; then there are the eerie strings on the soundtrack, the car chase, suspicious people in the background. The tension between the characters, however, could have been emphasized to greater advantage, and should have been the main focus. Cattrall’s Bly just stands there as Williams’ Ruth throws fits of frustration, while Brosnan’s Lang sits and looks on. The best scene, in terms of suspense, is carried by Wilkinson’s Emmett, fiddling nervously with his fingers while sternly rebutting the ghost writer’s insinuations. The penultimate scene in which the ghost writer passes on a note at the book presentation to confront Ruth about his discovery is utterly senseless – it fails as the final act and remains implausible from the ghost writer’s perspective (or we have to acknowledge that he is just plain stupid). To bring home the conspiracy hypothesis, the ghost writer gets run over while trying to escape with Lang’s original (coded) manuscript.

Even on the level of a thriller the movie falters. Polanski employs some of the usual ploys to create suspense: it rains a lot, skies are broodingly dark, much of the actions takes place on an isolated island, the ghost writer stays at an empty hotel, until a crowd of journalists and protesters swarm all over the place, Lang’s modern minimalist villa is menacingly impersonal; then there are the eerie strings on the soundtrack, the car chase, suspicious people in the background. The tension between the characters, however, could have been emphasized to greater advantage, and should have been the main focus. Cattrall’s Bly just stands there as Williams’ Ruth throws fits of frustration, while Brosnan’s Lang sits and looks on. The best scene, in terms of suspense, is carried by Wilkinson’s Emmett, fiddling nervously with his fingers while sternly rebutting the ghost writer’s insinuations. The penultimate scene in which the ghost writer passes on a note at the book presentation to confront Ruth about his discovery is utterly senseless – it fails as the final act and remains implausible from the ghost writer’s perspective (or we have to acknowledge that he is just plain stupid). To bring home the conspiracy hypothesis, the ghost writer gets run over while trying to escape with Lang’s original (coded) manuscript.

On a personal level, we might speculate that Polanski was driven to produce and direct an anti-American film. While editing the movie, he was himself under siege, i.e., under house arrest in Switzerland facing possible extradition on account of pending charges of sexual abuse going back over thirty years. Such a personal motivation may, in part, explain the rather one-sided perspective and why the moral dilemmas facing the various characters is so little explored. In the end, Adam Lang is no more than a mindless pawn in American imperialism, manipulated by his wife, both hungry for a figment of power and the easy comfort that comes with it. That is not to say that I personally condone the extradition of terrorist suspects so that they can disappear in detention camps until they confess under torture – or die. I do believe, however, that Polanski’s personal experience of facing extradition (in his mind, at least) on trumped up charges plausibly suggests that he sympathizes with the victims of Guatánamo Bay. Yet, America is not the embodiment of everything that’s wrong in this world. These are times in the grip of terrorism, which – whatever its motives or leanings – is easily identifiable as criminally evil. This film never addresses this side of the story, other than in politicians’ hollow sound bites. To your Chirping Cricket, that’s a missed opportunity.

The film – and the novel by Robert Harris on which it is based – poses some appropriate questions about the post 9-11 political landscape. Unfortunately, it never really explores these questions in any depth. It certainly is baffling that a Labour PM could have been such an American lapdog – especially at the time of the Bush administration. Adam Lang, however, remains a rather flat character, more of a womanizer and heavy drinker. We get no indication what motives him, why he is such a staunch pro-American, or what his thoughts are on the war on terror. We are led to believe that he merely became politically active through his wife Ruth, who was his trusted advisor for years. We get no indication either what motivates her, why she is throwing temper tantrums, or why she approaches the ghost writer for solace and sleeps with him. In the end, we learn that she has been a CIA agent from the start, recruited by Emmett, and thus her emotional instability becomes only more puzzling and her motivations even more obscure. There’s a hint at a rightist intellectual think-tank, Arcadia, with ties to the CIA and a weapons dealer in whose private jet Lang is flying. It is all tossed in our direction, perhaps even vindictively, for us to make sense of. But the moral quandaries, the fascinating grey area between good and bad, are left unaddressed. It is, for one, a government’s responsibility to protect its citizens, whether from terrorism or other menaces. How to implement national security without breaching human rights, international laws, and personal privacy, those are important questions from which this film shies away.

Even on the level of a thriller the movie falters. Polanski employs some of the usual ploys to create suspense: it rains a lot, skies are broodingly dark, much of the actions takes place on an isolated island, the ghost writer stays at an empty hotel, until a crowd of journalists and protesters swarm all over the place, Lang’s modern minimalist villa is menacingly impersonal; then there are the eerie strings on the soundtrack, the car chase, suspicious people in the background. The tension between the characters, however, could have been emphasized to greater advantage, and should have been the main focus. Cattrall’s Bly just stands there as Williams’ Ruth throws fits of frustration, while Brosnan’s Lang sits and looks on. The best scene, in terms of suspense, is carried by Wilkinson’s Emmett, fiddling nervously with his fingers while sternly rebutting the ghost writer’s insinuations. The penultimate scene in which the ghost writer passes on a note at the book presentation to confront Ruth about his discovery is utterly senseless – it fails as the final act and remains implausible from the ghost writer’s perspective (or we have to acknowledge that he is just plain stupid). To bring home the conspiracy hypothesis, the ghost writer gets run over while trying to escape with Lang’s original (coded) manuscript.

Even on the level of a thriller the movie falters. Polanski employs some of the usual ploys to create suspense: it rains a lot, skies are broodingly dark, much of the actions takes place on an isolated island, the ghost writer stays at an empty hotel, until a crowd of journalists and protesters swarm all over the place, Lang’s modern minimalist villa is menacingly impersonal; then there are the eerie strings on the soundtrack, the car chase, suspicious people in the background. The tension between the characters, however, could have been emphasized to greater advantage, and should have been the main focus. Cattrall’s Bly just stands there as Williams’ Ruth throws fits of frustration, while Brosnan’s Lang sits and looks on. The best scene, in terms of suspense, is carried by Wilkinson’s Emmett, fiddling nervously with his fingers while sternly rebutting the ghost writer’s insinuations. The penultimate scene in which the ghost writer passes on a note at the book presentation to confront Ruth about his discovery is utterly senseless – it fails as the final act and remains implausible from the ghost writer’s perspective (or we have to acknowledge that he is just plain stupid). To bring home the conspiracy hypothesis, the ghost writer gets run over while trying to escape with Lang’s original (coded) manuscript.On a personal level, we might speculate that Polanski was driven to produce and direct an anti-American film. While editing the movie, he was himself under siege, i.e., under house arrest in Switzerland facing possible extradition on account of pending charges of sexual abuse going back over thirty years. Such a personal motivation may, in part, explain the rather one-sided perspective and why the moral dilemmas facing the various characters is so little explored. In the end, Adam Lang is no more than a mindless pawn in American imperialism, manipulated by his wife, both hungry for a figment of power and the easy comfort that comes with it. That is not to say that I personally condone the extradition of terrorist suspects so that they can disappear in detention camps until they confess under torture – or die. I do believe, however, that Polanski’s personal experience of facing extradition (in his mind, at least) on trumped up charges plausibly suggests that he sympathizes with the victims of Guatánamo Bay. Yet, America is not the embodiment of everything that’s wrong in this world. These are times in the grip of terrorism, which – whatever its motives or leanings – is easily identifiable as criminally evil. This film never addresses this side of the story, other than in politicians’ hollow sound bites. To your Chirping Cricket, that’s a missed opportunity.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.